Every month I put together a series of Illustrated Booknotes on books that I’ve read and are useful to me.

This month we’re looking at Ultralearning by Scott H. Young, how you can master hard skills, outsmart the competition, and accelerate your career.

From the foreword by James Clear

He has a bias toward action

He isn’t focused on simply soaking up knowledge. He is committed to putting that knowledge to use. Approaching learning with an intensity and commitment to action is a hallmark of Scott’s process.

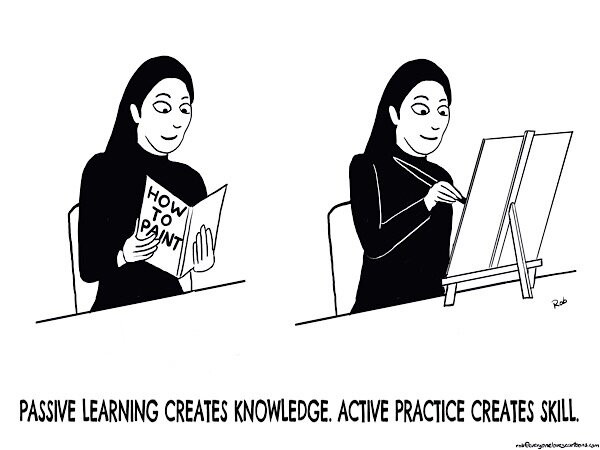

Directness is the practice of learning by directly doing the thing you want to learn. Basically, it’s improvement through active practice rather than through passive learning. The phrases learning something new and practicing something new may seem similar, but these two methods can produce profoundly different results.

Passive learning creates knowledge. Active practice creates skill.

Finally, deep learning is possible. Paul Graham, the famous entrepreneur and investor, once noted, “In many fields a year of focused work plus caring a lot would be enough.”

Similarly, I think most people would be surprised by what they could accomplish with a year (or a few months) of focused learning. The process of intense self-directed learning can fashion skills you never though you could develop.

Start speaking the very first day.

*with any of these concepts, think how could this apply to me? You may not want to learn a language, but how could you start doing XXXXX on the very first day?

Don’t be afraid to talk to strangers. Use a phrase book to get started; save formal study for later. Use visual mnemonics to memorise vocabulary.

What struck me were not the methods but the boldness with which he applied them.

Lewis was fearless, diving straight into conversations and setting seemingly impossible challenges for himself.

Aggressive self-education

“I wanted the colours to pop.” So he researched colour theory and intensively studied other artists to see how they used colours to make things visually interesting.

Eric Barone - video game builder

Because this project was my own vision and design, it rarely felt painful, even if it was often challenging. The subjects felt alive and exciting, rather than stale chores to be completed. For the first time ever, I felt I could learn anything I wanted to with the right plan and effort. The possibilities were endless, and my mind was already turning toward learning something new.

My goal for the project wasn’t to get a job but to see what was possible.

How much better could I be if I held nothing back and optimized everything around learning a new language as intensely and effectively as possible?

What if, instead of just hoping you’d practice enough, you don’t give yourself an escape route?

I had enjoyed drawing as a kid, but like most people’s attempts, any faces I drew looked awkward and artificial. I had always admired people who could quickly sketch a likeness whether it be street-side caricaturists to professional portrait painters. I wondered if the same approach to learning MIT classes and languages could also apply to art.

I decided to spend a month improving my ability to draw faces. My main difficulty, I realised, was in placing the final features properly. A common mistake when drawing faces, for instance, is putting the eyes too far up the head. Most people think the sit in the top two-thirds of the head. In truth, they’re more typically halfway between the top of the head and the chin. To overcome these ad other biases, I did sketches based on pictures. Then I would take a phot of the sketch with my phone and overlay the original image on top of my drawing. Making the photo semi transparent allowed me to see immediately whether the lead was too narrow or wide, the lips too low or too high or whether I had put the eyes in the right spot. I did this hundreds of times, employing the same rapid feedback strategies that had served me well with MIT classes. Applying this and others strategies, I was able to get a lot better at drawing portraits in a short period of time.

Ultratlearners had a lot of spread traits. They usually worked alone, often toiling for months and years without much more than a blog entry to announce their efforts. Their interested tended toward obsession. They were aggressive about optimising their strategies, fiercely debating the merits of esoteric concepts such as interleaving practice, leech thresholds, or keyword mnemonics. Above all, they cared about learning. Their motivation to learn pushed them to tackle intense projects, even if it often came at the sacrifice of credentials or conformity.

What if you could create a project to quickly learn the skills to transition to a new role, project, or even profession? What if you could master an important skill for your work? What if you could be knowledgable about a wide variety of topics?

What if you could become good at something that seems impossible to you right now?

Ultralearning isn’t easy. It’s hard and frustrating and requires stretching outside the limits of where you feel comfortable. However, the thins you can accomplish make it worth the effort.

Chapter 2 - Why Ultralearning Matters

Ultralearning: A strategy for acquiring skills and knowledge that is both self-drenched and intense.

Ultralearning is intense. All of the ultralearners I met took unusual steps to maximise their effectiveness in learning. Fearlessly attempting to speak a new language you’ve started to practice, systemically drilling tens of thousands of trivia questions, and iterating through are again and again until it is perfect is hard mental work. It can feel as though your mind is at its limit..

An intense method might also produce a pleasurable state of flow, in which the experience of challenge absorbs your focus and you lose track of time. However, with Ultralearning, deeply and effectively learning things is always the main priority.

How many of us have dreams of playing an instrument, speaking a foreign language, becoming a chef, writer or photographer? Your deepest moments of happiness don’t come from doing easy things; they come from realising your potential and overcoming your own limiting beliefs about yourself. Ultralearning offers a path to master those things that will bring you deep satisfaction and self-confidence.

“Average is over” - Tyler Cowen- economist

Because of increased computerisation, automation, outsourcing, and regionalisation, we are increasingly living in a world in which the top performers do a lot better than the rest.

If you can master the personal tools to learn new skills quickly and effectively, you can compete more successfully in this new environment. That the economic landscape is changing may not be a choice any of us has control over, but we can engineer out response to it by aggressively learning the hard skills we need to thrive.

Technology exaggerates both the vices and the virtues of humanity. Our vices are made worse because now that are downloadable, portable, and socially transmissible. The ability to distract or delude yourself has never been greater, and as a result we are facing a crisis of both privacy and politics..

Spaced repetition

By choosing a valuable skill and focusing on quickly developing proficient, you can accelerate your normal career progression.

Ultralearning is a potent skill for dealing with a changing world. The ability to learn hard things quickly is going to become increasingly valuable, and this it is worth developing to whatever extent you can, even if it requires some investment first.

Learning, at its core, is a broadening of horizons, of seeing things that were previously invisible and of recognising capabilities within yourself that you didn’t know existed. I see no higher justification for pursuing the intense and devoted efforts of the ultralearners than this expansion of what is possible. What could you learn if you took the right approach to make it successful?

Who could you become?

The core of the ultralearning strategy is intensity and a willingness to prioritize effectiveness.

What matters is the intensity, initiative, and commitment to effective learning, not the particulars of your timetable.

The ability to acquire hard skills effectively and efficiently is immensely valuable.

Public speaking is a metaskill. It’s the kind of skills that assist with other skills: confidence, storytelling, writing, creativity, interviewing skills, selling skills. It touches on so many different things.

Once, when faced with the choice between polishing an existing speech and creating a brand-new one from scratch, de Montebello asked what he should do. Gendler’s response was to do whichever was scariest for him.

Another friend with a background in theater gave him tips on stage presence. He took do Montebello through his speech and showed how each word and sentence indicated movement that could be translated to where he moved on the stage.

Make me care.

What differentiated de Montebello wasn’t that he though he could go from near-zero experience to the finalist for the World Championship in six months. Rather, it was his obsessive work ethic. His goal wasn’t to reach some predetermined extreme but to see how far he could go.

Ultralearning in my view, works best when you see it through a simple set of principles, rather than trying to copy and paste exact steps or protocols.

Aggressively paced coding boot camps can get participants up to a level where they can compete for jobs much faster than those with a normal undergraduate degree.

Over the long term, the more ultralearning projects you do, the larger your set of general metalearning skills will be. You’ll know what your capacity is for learning, how you can best schedule your time and manage your motivation, and you’ll have well-tested strategies for dealing with common problems. As you learn more things, you’ll acquired more and more confidence, which will allow you to enjoy the process of learning more with less frustration.

Determining why, what, and how

I find it useful to break down metalearning research that you do for a specific project into three questions: “Why?” “What?,” and “How?” Refers to understanding your motivation to learn. If you know exactly why you want to learn a skill or subject, you can save a lot of time by focusing your project on exactly what matters most to you. “What?” Refers to the knowledge and abilities you’ll need to acquire in order to be successful. Breaking things down into concepts, facts, and procedures can enable you to map out what obstacles you’ll face and how best to overcome them. “How?” Refers to the resources, environment, and methods you’l use when learning. Making careful choices here can make a big difference in your overall effectiveness.

Why?

The first question you try to answer us why you are learning and what that implies for how you should approach the project. Practically speaking, the projects you take on are going to have one of two broad motivations: instrumental and intrinsic.

What?

Once you’ve gotten a handle on why you’re learning, you can start looking at how the knowledge in your subject is structured. A good way to do this is to write down on a sheet of paper three columns with the headings “Concepts,” Facts,” and “Procedures.” Then brainstorm all the things you’ll need to learn.

Concepts are ideas that you need to understand in flexible ways in order for them to be useful.

Facts are anything that suffices if you can remember them at all.

Procedures are actions that need to be performed and may no involve much conscious thinking at all.

Once you’ve finished your brainstorm, underline the concepts, facts, and procedures that are going to be most challenging. This will give you a good idea what the major learning bottlenecks are going to be and can start you searching for methods and resources to overcome those difficulties.

When I started my portrait-drawing challenge, for instance, I knew that success would depend highly on how accurately I could size and place facial features. Most people can’t draw realistic faces because if those attributes are off even slightly (such as making a face too wide or the eyes too high), they will instantly look wrong to your sophisticated ability to recognise faces. Therefore, I got the idea of doing lots and lots of sketches and comparing them by overlaying the reference photos. That way I could quickly diagnose what kinds of errors I was making without having to guess. If you can’t make these kinds of predictions and come up with these kinds of strategies just. Yet, don’t worry. This is the kind of long-term benefit of metalearning that comes from having done more projects.

Benchmarking

The way to start any learning project is by finding the common ways in which people learn the skill or subject.

The quality of materials you use can create orders-of-magnitude differences in your effectiveness. Even if you’re eager to start learning right away, investing a few hours now can save you dozens or hundreds later on.

The 10 percent rule

You should invest approximately 10 percent of your total expected learning time into research prior to starting.

The best research, resources, and strategies are useless unless you follow up with concentrated efforts to learn.

Focus

In the realm of great intellectual accomplishments an ability to focus quickly and deeply is nearly ubiquitous.

The struggles with focus that people have generally come in three broad varieties: starting, sustaining, and optimising the quality of one’s focus. Ultralearners are relentless in coming up with solutions to handle these three problems, which form the basis of an ability to focus well and learn deeply.

Failing to start focusing - procrastination

The first problem that many people have is starting to focus. The most obvious way this manifest itself is when you procrastinate: instead of doing the thing you’re supposed to, you work on something else or slack off. For some people, procrastination is the constant state of their lives, running away from one task to another until deadlines force them to focus and then having to struggle to get the job done on time.

*I need to have tighter deadlines and the accountability to back them up.

Much procrastination I’d unconscious. You’re procrastinating, but you don’t internalise it that way. Instead you’re “taking a much-needed break” or “having fun, because life can’t always be about work all the time.” The problem isn’t those beliefs. The problem is when they’re used to cover up the actual behaviour. - you don’t want to do the thing you need to be focusing on, either because you are directly averse to doing it or because there’s something else you want to do more. Recognising that you’re procrastinating is the first step in avoiding it.

Make a mental habit of every time you procrastinate; try to recognize that you are feeling some desire not to do that task or a stronger desire to do something else. You might even want to ask yourself which feeling is more powerful in that moment - is the problem more that you have a strong urge to do a different activity (e.g., eat something, check your phone, take a nap) or that you have a strong urge to avoid the thing you should be doing because you imagine it will be uncomfortable, painful, or frustrating? This awareness is necessary for progress to be made, so if you feel as though procrastination is a weakness of yours, make building this awareness your first priority before you try to fix the problem.

A first crutch comes from recognizing that most of what is unpleasant in a task (if you are averse to it) or what is pleasant about an alternative task (if you’re drawn to distraction) is an impulse that doesn’t actually last that long. If you actually start working or ignore. A potent distractor, it usually only takes a couple minutes until the worry starts to dissolve, even for fairly unpleasant tasks. Therefore, a good first crutch is to convince yourself to get over just the few minutes of maximal unpleasantness before you take a break. Telling yourself that you need to spend only five minutes on the task before you can stop and do something else is often enough to get you started. After all, almost anyone can endure five minutes of anything, no matter how boring, frustrating, or difficult it may be. However once you start, you may end up continuing of longer without wanting to take the break.

If you find yourself setting a daily schedule with chunked hours and then frequently ignore it to do something else, go back to the start and try building back up again with the five-minute rule and then the Pomodoro Technique.

K. Anders Ericsson, the researcher behind deliberate practice, argues that flow has characteristics that are “inconsistent with the demands of deliberate practice for monitoring explicit goals and feedback and opportunities for error correction.

Fifty minutes to an hour is a good length of time for many learning tasks.

If I have difficult reading to do, I will often make an effort to jot down notes that reexplain hard concepts for me. I do this mostly because, while I’m writing, I’m less likely to enter into the state of reading hypnosis where I’m pantomiming the act of reading while my mind is actually elsewhere.

More intense strategies, whether solving problems, making something, or writing or explaining ideas aloud, are harder to do in the background of your mind, so there are fewer opportunities for distractions to creep in. ****apply this to my life!!!

A random worry about some future event might bubble up, let’s say, but you know you shouldn’t stop the activity you’re working on right now in order to deal with it. Here the solution is to acknowledge the feeling, be aware of it, and gently adjust your focus back to your task and allow the feeling to pass.

If you “learn to let it arise, note it, and lease it or let it go,” this can diminish the behaviour you’re trying to avoid.