Would you like to be able to draw your own cartoon strip?

We’re all familiar with classic comic strips such as Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes, and we may even have pinned examples of them up on your fridge or at work - in the case of Dilbert.

You may have your own personal favourite that you’ve been following for ages and have gotten to know the characters quite well.

Maybe you’ve fancied drawing your own one, but have been put off by thought that it’s too difficult or takes too much time. It certainly more complex than drawing a single one-off gag cartoon, but there’s no need to be put off.

No fear!

What if drawing your own strip cartoon turned out to be not as much hassle as you initially thought?

This guide will break it down and take you through all the stages you need to create your own cartoon.

If you get the chance, you’re encouraged to draw along as you read this article.

Whenever you see a ‘over to you’ heading, that’s your cue to think, make notes or doodle.

It’s more effective to do this as you read along, as you can try it out on the spot. We often read things and intend to return to them later only for life to get in the way.

There will be some handy free tips/key points as we go along

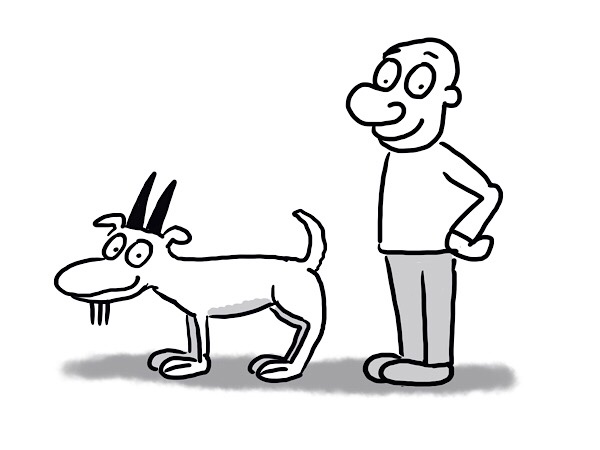

Meet Gerald the Goat

To look at comic strips, we’re going to enlist the help of Gerald the Goat and Stan.

I’ve been drawing the Gerald the Goat strip for a couple of years now. I’m going to use some examples from it to illustrate this article.

What is a strip cartoon?

First, before we get started creating, what exactly is a strip cartoon?

A strip cartoon is a short series of panels, usually three or four, that communicate a brief story -usually ending with a punch line.

Most strips have recurring characters and some feature an underlying storyline that continues from strip to strip.

As the readers learn more about the characters lives as the story develops over time, a strong bond develops between them.

Readers often have their favourite cartoon strip and the connection they have to it can spread over years in the case of a long running strip.

Can connect with and develop a strong bond between the characters and the readers. The readers get to know more and more about the characters over time, as the story continues.

A strip cartoon doesn’t have to be overly humorous. Fred Basset is a good example of a strip that has a very gentle sense of humour, and relies more on observation of the dog and his family’s lives, rather than strong gags

Let’s keep it simple at first

First of all, let’s keep it simple by creating a one-off strip cartoon. They’ll be some suggestions for developing your characters and storylines later on.

When creating a strip, the first thing to think up is the setting, and then put to together a cast of characters.

Alternatively you could create a distinct character and then work out what location/setting they inhabit.

Settings

Popular settings include:

-Kids life (Calvin and Hobbes, Peanuts)

-Work (Dilbert)

Over to you:

Think of three possible settings for your cartoon.

Characters

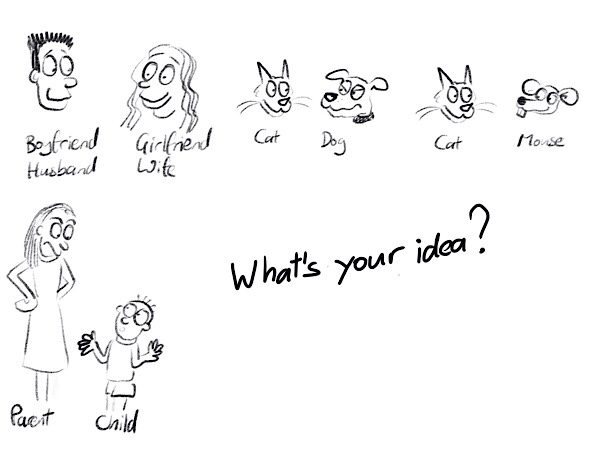

With any cartoon you need some characters. You’ll need at least at least two so that they can interact with each other.

Let’s look at some common pairings.

Garfield: Garfield (pet) and Jon (owner)

Peanuts: Snoopy (pet) and Charlie Brown (owner)

Over to you:

Can you think up any other pairings?

Here are a few:

-Boss and co-workers

-boyfriend and girlfriend

-cat and dog

But I can’t draw!

You may be thinking, this is nice but I can’t draw.

Well, what do you mean ‘I can’t draw?’

I find that when people say that they can’t draw, ‘can’t’ can mean a bunch of things from ‘can’t find one end of a pencil from another’ to ‘I’m not as good as a professional cartoonist’. I’m guessing that if you’ve found this article then at least you know how to draw a little bit.

You don’t have to be a great artist to produce a strip cartoon.

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel here - there’s plenty of room for another cat or dog cartoon.

Besides, we’re not aiming for perfection to dazzling artwork here - we’re simply aiming to introduce you to the wonderful world of strip cartoons.

Use personal experience to create a character pair

You could try using your own personal experience to come up with some ideas for characters.

Do you have a pet of your own?

Do you work in an office?

Do you have a particular hobby or interest?

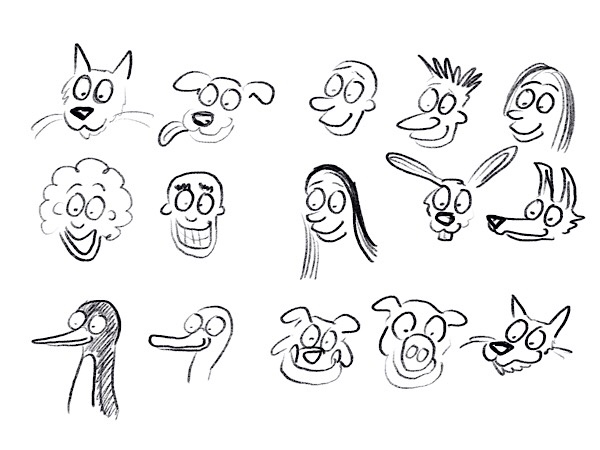

Just doodle!

If you can’t come up with any ideas for a potential character, just start doodle lots and lots of simple characters and see where that leads.

If one in particular strikes, then doodle lots of variants of it until one sticks.

Coming up with stories

Now that you have a couple of characters we have to think up a story for them.

Let’s think of some common situations for the character.

But first, let me mention…

The idea muscle

One of the key features of this article is the idea of the ‘idea muscle’. Thinking up ideas is like building muscles, it takes some skill and application, but the more you do it the better you become.

This process is not necessarily easy, just as when you start exercise of any sort, however it is not supposed to be a hard slog either. If you put in a little time and do the some of the exercises consistently you’ll start to see results.

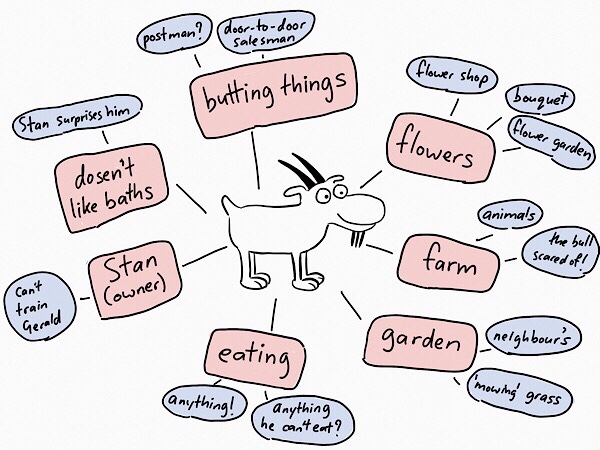

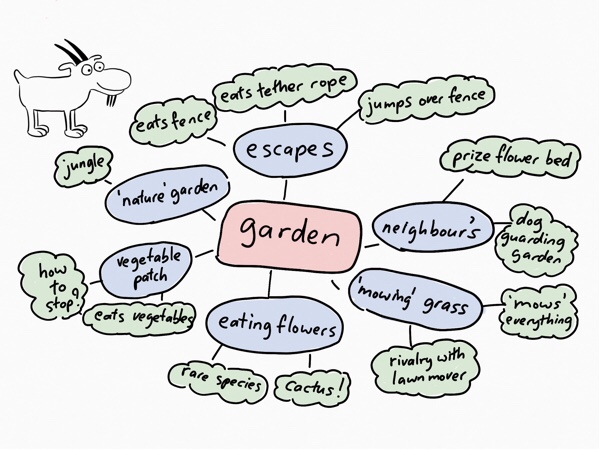

Mindmap

Let’s try a mindmap featuring Gerald. I wrote down any particular ideas or situations associated with him that came to mind. It dosen’t matter whether they’re good ideas at this point, the most important thing is to write them down. Don’t pause to think for too long!

You can choose one of the ideas and do a new mind map to make it even more focused.

Over to you:

Try out your own mindmap featuring your character. Remember don’t pause for thought - write down whatever comes to mind.

Create a character profile

Another really good way to get to know your character is to create a profile/avatar for them.

Here is an example featuring Gerald

Name: Gerald the goat

Where does he/she live?: Stan’ garden (well, he’s supposed to anyway...)

What does he do? Eats things...almost anything, especially people’s flower beds...

What does he like? Eating, butting people

What does he dislike? The bull

Describe personality in a sentence: Gerald is a little bit of anarchy in goat-form.

Here’s a blank profile you can use. Feel free to add additional information, and to add as much detail as you like. The more detail you add the more richer character you’ll create - and the better you’ll get to know them

Name:

Where does he/she live?

What does he/she do?

What does he/she like?

What does he/she dislike?

Describe his/her personality in a sentence:

Get started

The most important thing about trying to create to strip cartoon is to simply get started. Try doodling lots of characters and see which ones appeal to you.

One way to force yourself to do this, is to set a timer for a couple of minutes and doodle as many different characters as you can during that time. You can set yourself a theme if you want to narrow it down, such as animals or children.

Drawing characters

After you’ve created your character, try making a few notes about their appearance to help you for future reference.

Practice drawing your characters

In a cartoon strip the characters appear from panel to panel, and strip to strip, so it’s important that the characters always look the same to maintain this sense of continuity.

Start to practice drawing your characters again and again in the same pose. Start off by drawing a side profile, as that’s the more useful to draw when having the characters talking with another character

If you’re working with a drawing tablet, you might be wondering why you don’t simply copy and paste the characters. Drawing the characters helps to build the muscle memory so that you can draw them at will later on. This will also help when you try to draw the characters in new poses,

as you will have an instinctive idea of how the characters proportions should look even you’ve previously drawn them a lot.

Over to you:

Choose an existing character or one you generated from the earlier exercise. Practice drawing them a bunch of times like the examples featuring Gerald and Stan above.

Expressions and Mannerisms

Imagine your characters carrying out conversations with each other, or thinking about different events. You could even try putting yourself into one of the characters shoes and joining in the conversation itself. Think of this as playful, rather than silly.

Try day-dreaming and putting yourself into the characters shoes. Imagine what you might do if you were in their place.

Everyday life

Popular cartoons that work well are usually the ones that comment on everyday life and people’s habits and quirks - i.e. thing that we are already very familiar with. You don’t have to think of anything too exotic. Even if you have an exotic setting, you can still have the characters commenting on the everyday nature of that exotic setting.

Other situations

What other every day situations can you think up?

They might include: catching a train, waiting in a queue, getting wet in the rain etc.

Just doodle!

If you can’t come up with any ideas, start doodling your characters in funny situations and see what ideas that might spark. Don’t forget that a cartoon gives you a licence to exaggerate the characters and their setting.

Collect different situations to use

As you keep drawing your characters you’ll come across situations that can be recycled and used again and again. In the case of Gerald the goat, this would include his attempts to eat flower beds, running away from the bull etc.

You can keep a note of these situations and bring them out from time to time if you are stuck for ideas.

Make a list of questions about your character

Here are a few examples featuring Gerald the goat.

-What does he want to eat?

-How is he going to get the food?

-What might stop him from getting the food?

-what might happen after he gets the food?

Everyday life

Popular cartoons that work well are usually the ones that comment on everyday life and people’s habits and quirks - i.e. thing that we are already very familiar with. You don’t have to think of anything too exotic. Even if you have an exotic setting, you can still have the characters commenting on the everyday nature of that exotic setting.

Opening panel method

This is a way to get started on a strip when we haven’t yet got an idea for the ending. Draw a situation with one or more characters in the first panel and what comes to mind for the rest of the strip.

Closing frame method

This is the reverse of the starting frame method. This time you trying to think of the gag or punch line last and then work backwards to think up the rest of the cartoon.

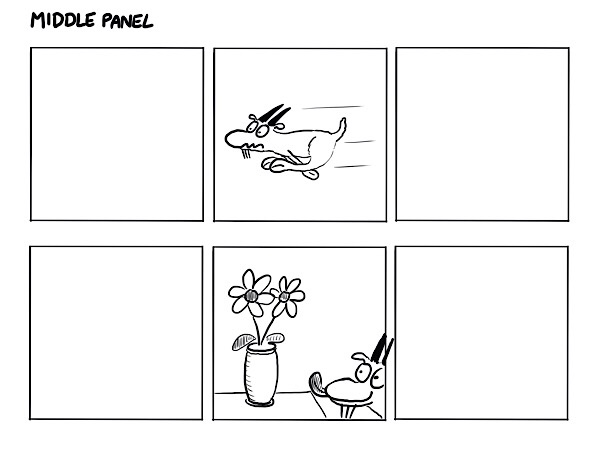

Middle frame method

For this one draw something happening in the middle frame and see if that sparks any ideas for either the punchline or the opening.

Layout

Composition

The composition of your cartoon is how your arrange your characters, any props and the setting throughout the strip. It’s important to think about how clear the composition is, as if it is muddle then it makes it hard for your reader to understand what is going on or what the gag is.

A reader only scans the cartoon with their eyes for a brief moment, and will only spend a couple of seconds trying to work out what is going on in the cartoon. So you have to make sure that the composition of your cartoon gets the idea across to the reader immediately.

Try to convey a lot of information with the minimum amount of lines and detail

Don’t get distracted

Don’t worry at first about what size you should draw the strip. Draw your characters and their setting at whatever size feel comfortable for you. You can experiment with the size of the strip later on.

Be careful not to spend too much time over particulars such as what equipment to use or how the cartoon finally finally look when polished. This can distract away form the most important task of all - to start drawing your cartoon.

To add:

background

colour

frames

Make sure your character’s eyes are looking in the right direction.

Settings

The setting for your characters can be simple - the most important thing is to set the scene quickly so that your readers know what is going on.

Backgrounds need to give enough detail to help set the story, but not too much so as to distract from the characters and the story.

Foreground, mid-ground, background

How you position characters within the frames changes the message and the feel of the story.

To re-write:

The foreground tends to lead the viewer into the picture and conveniently frames the setting with a window-like boundary that assist focus. Most of the cartoon’s action, dialogue and interaction reside in the midground. It is also where a full, objective overview of the setting can be made. The background establishes the setting by anchoring its features. The placement of the horizon line here determines scale, depth and perspective, unifying all the elements of the picture and ensuring that their juxtaposition makes sense.

The important point about drawing the setting is to only include what is necessary to tell the story.

We are so familiar with a range of surroundings - our homes, offices, shops and streets - that it does not require many everyday objects to set a scene.

As long as your readers already know the context of the cartoon, then you don’t need to include so much detail

A squiggle could represent a row of trees, rectangles with some simple markings show a row of buildings, a TV shows a living room, some simple desks an office.

Think about what the minimum number of clues you need to set the scene.

As you draw everyday objects, add them to your reference library. You can refer to them again and again in the future.

Lettering/speech bubbles

We read dialogue from left to right or top to bottom.

Words and pictures work together

In any sort of cartoon, words and pictures work together to get the idea or gag across, and shouldn’t be considered separately.

A character’s facial expression speaks as much as the words that come out of it.

Before you start drawing your first cartoon, have the script drafted out and some rough sketches for each frame

Do your lettering first, and then draw the speech or thought bubble around it.

It doesn’t matter whether you handwrite your own lettering or use the lettering in an app such Procreate or Sketches.

Be careful not to cram too much writing into one bubble.

Different fonts can really change the tone of the cartoon.

The more text you have, the less space available for the art - and vice versa.

Experiment with using different fonts, font sizes, placing the text is different places within the frame.

Try many different ones until you come up with a style that suits you.

Let your lettering breath

Make sure to leave some space between your lettering and the surrounding speech/thought bubble so that it is easy to read.

Don’t write too many words in the bubble, as it can become too crowded and difficult to read.

Draft your speech bubbles, the same way you’d draft a drawing. Look over your writing and see if there are any unnecessary words you could remove. Don’t always settle for the first version.

To rewrite:

‘A’ begins the conversation as his speech is at the top of the frame. At the end of the sentence, the eye naturally flows to the second bubble belonging to the other character. The first speaker’s second bubble is joined to the first by a path dispelling the need for two pointers heading for one head.

Expression through bubbles

Speech bubbles can be made more dramatic with jagged edges

It may be necessary for a character to make a longer speech and you may wish to. Adopt a device for effective splitting to allow the character and the reader a break.

Continuing your strip

How can I keep the strip going?

It can be quite a daunting thought, trying to maintain a cartoon strip. However, with a little planning there’s not reason for this to be the case.

It’s good to have a set process in hand/system to follow to ensure that you turn your strip on a weekly basis or however often you want to produce it.

How can I keep creating new ideas?

As you get to know your characters and their world more and more you’ll find that they take on a life of their own and ideas will start to appear automatically. This doesn’t always mean that it will be easy to come up with ideas, but some ideas will present themselves of their own accord.

Once you get a good idea for a story arc, then plots will come from that that you can use in individual strips.

How can I make it more efficient?

I think that it’s very useful to plan out your story line in advance

There can be some reoccurring story lines. Gerald has to have a bath, Gerald attempting to break into the annual garden show etc.

Get to know your characters

As the creator of the strip, you should get to know all of your characters really well. Unless you know your characters intimately and they come alive for you - there’s not way they’ll be able to come alive for your readers.

Story arcs

*As a cartoon strip is usually a series of ongoing stories, how can you generate some ideas for stories that will produce lots of ideas for individual strips?

What could be the basis of an ongoing story?

Let’s look at an example.

A leopard has escaped from the zoo.

What are some ideas that could form the basis of individual strips?

-the leopard tres to catch Gerald

-Gerald has to escape from the leopard

-Gerald has to hide from the leopard

-Gerald tries to reason with the Leopard

-Rex the police dog (a supporting character talks with the leopard)

-Gerald tries to capture the leopard

-Gerald fails to capture the leopard - and the subsequent consequence

-Someone else captures the leopard

-The leopard is captured

-the leopard goes back to the zoo

-Gerald visits the leopard in the zoo.

Over to you

What I’ve for your characters could produce a good story?

Here are a few ideas:

-someone going on a blind date

-a new person joining the office

-a new pet joining the family

-a dog wants to play

-it’s a really rainy day

Creating a cast of characters

Over to you:

Build up a reference library

To help make drawing your strip more efficient in the future, collect different backgrounds that you can re use form time to time. This also applies to everyday objects as well.